Cursed by Your Own Mind

The Imposter Curse - Capgras Delusion

Imagine your mother. She looks like your mother. Has her eyes, her voice, even her smile. But something is wrong. The familiarity is only skin-deep, a mask stretched over a stranger. Your brain whispers that this woman is not your mother at all, but an actor, an imposter.

First described in 1923 by French psychiatrist Joseph Capgras, and his intern Jean Reboul-Lacaux, as l’illusion des sosies or the “illusion of doubles”, Capgras syndrome, convinces patients that their loved ones have been replaced by imposters, strangers in a familiar skin. Their paper was based on the case of a 53-year-old woman diagnosed as a “paranoid megalomaniac”, believing she was famous, wealthy, of royal lineage, superior to those around her, what might today overlap with features of narcissism or delusional disorder. Although this woman, Madame M, had lost 3 of her children, she refused to believe they had really died, rather they had been abducted instead, while she was convinced that her only remaining child had been replaced by a lookalike. Capgras delusion, also known as Capgras syndrome, is one of the most common of the many delusions associated with the misidentification of people, places and objects, collectively known as delusional misidentification syndrome (DMS), and is one of the clearest examples of how a disruption in brain connectivity can distort the construction of reality.

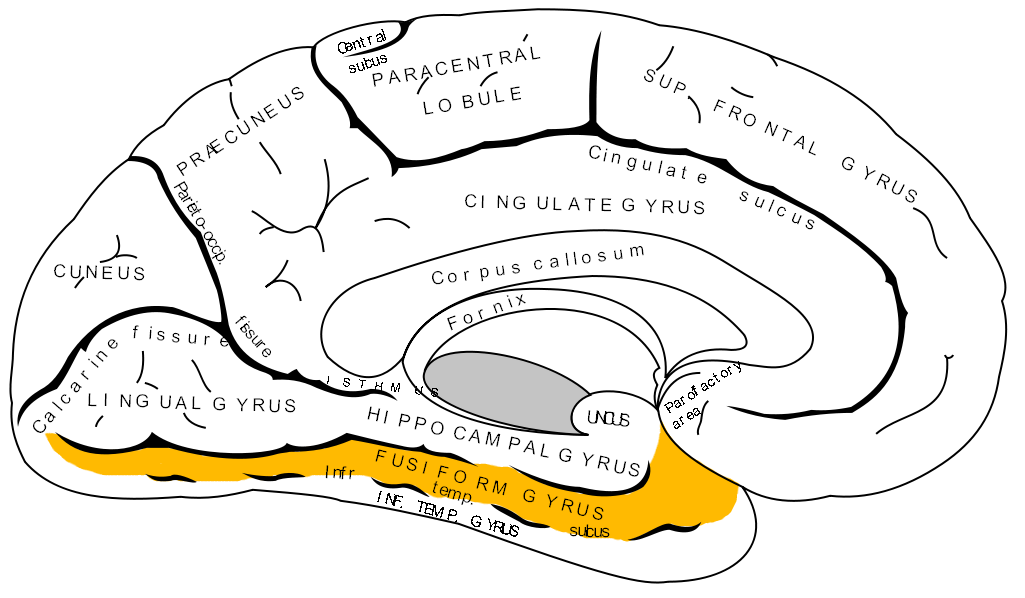

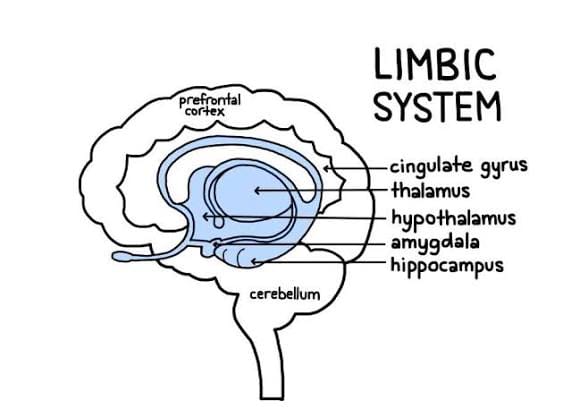

Normal face recognition can be broken into two steps: perceptual recognition and affective tagging. Perceptual recognition is the brain’s process of identifying and making sense of sensory information and giving it meaning involving taking the information, dividing it up and then recombining them into a coherent whole, often using past background knowledge and experiences to fathom what you are perceiving. The inferior temporal cortex, located within the cerebral cortex, is responsible for processing visual stimuli, with the fusiform face area (FFA) within the fusiform gyrus, specifically responsible for facial recognition and perception crucial for facial recognition. Affective tagging is the way in which the brain processes experiences and content by “tagging” them and storing them along with memories to enhance retention and influence future decision making. The limbic system is essential in this: during an emotionally arousing event, the amygdala, responsible for processing emotions, is activated which strengthens synapses, or electrical impulses, involved in memory function, such as the hippocampus, thus enhancing neuroplasticity. The “emotional tag” associated with that specific event or sensory experience helps to transform transient memories into stronger, long-lasting ones compared to neutral information (long vs short term memory storage). This means we can effectively learn from experiences and develop appropriate responses as our limbic system generates an autonomic, emotional response, and in the case of the facial recognition of our loved ones, the feeling of familiarity and attachment.

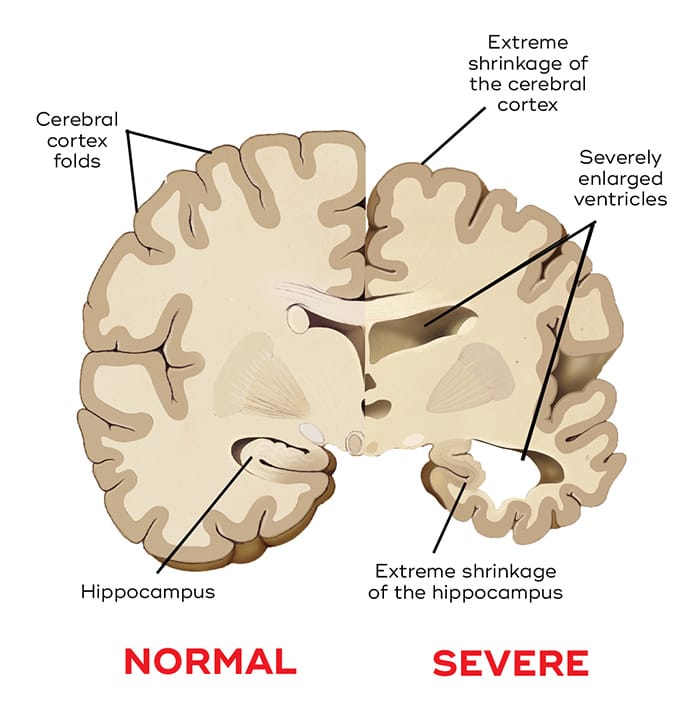

In Capgras delusion, the first stage, perceptual recognition, remains intact; the second, however, breaks down. Patients can identify a face correctly, but the usual autonomic response is absent. This can be measured as skin conductance or galvanic skin response, also known as electrodermal activity (EDA), referring to the measurement of electrical conductivity on the skin which changes according to sweat gland activity triggered by the autonomic nervous system. EDA can be measured by electrodes on the skin and is used to understand physiological and emotional responses – these are commonly used in areas like polygraph testing in lie detector tests. Displayed through irregular skin conductance responses (SCR), their brain processes the face as visually familiar but emotionally alien. This has been described as “recognition without affect” in contrast to s neurological condition called prosopagnosia which, in many cases, is “affect without recognition.” Prosopagnosia, stemming from the Greek words prosōpon “face” and agnōsia “ignorance”, is a condition in which patients cannot consciously recognise faces, yet still show an unconscious emotional response to familiar individuals, a feature of some degenerative dementias, such as Alzheimer’s disease and semantic dementia.

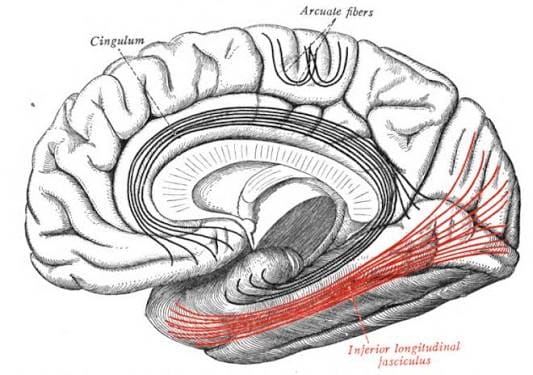

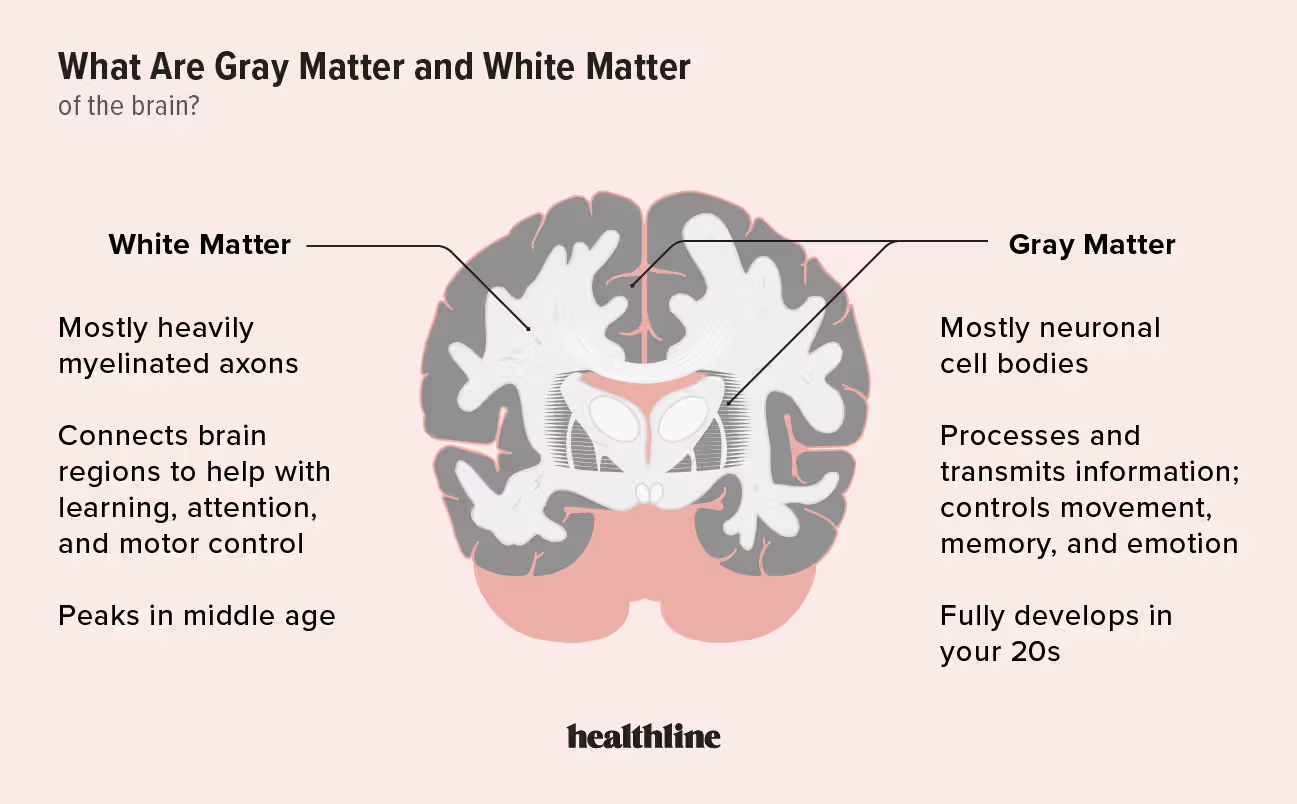

This emotional disconnection can be caused by an array of mechanisms. White matter: a key component of the brain, located in the deeper regions of the brain underneath the grey matter. It consists of bundles of nerve fibres, or axons, covered in a fatty insulation called myelin, which act as a communication highway allowing different parts of the brain to communicate with each other. Lesions or degeneration in pathways linking the FFA to the amygdala, via the inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF) connecting the temporal and occipital lobes where the FFA and amygdala are located respectively, can interrupt signals between the two thus interrupting the transfer of emotional salience. Although not a potential direct cause of Capgras syndrome, frontal lobe dysfunction can have a significant impact on dealing with the delusion. The frontal lobe, and more specifically the prefrontal cortex located at the front of it, is the brain’s “command centre” and is crucial for complex cognitive functions, such as decision making and judgement which may prevent patients from rejecting the false belief even when it conflicts with knowledge.

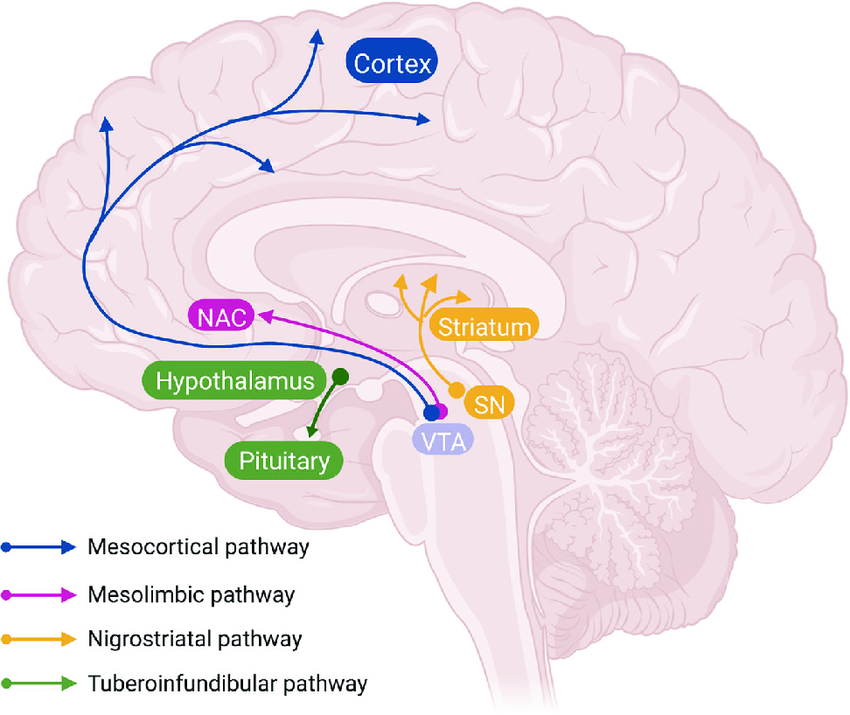

Another thing to consider is the neurochemical factor: In psychosis related Capgras, for instance, in a patient suffering from schizophrenia, the brain misinterprets a small error as something hugely important due to a chemical imbalance. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter involved in reward and motivation. In psychosis, dopaminergic pathways, such as the mesolimbic pathway vital for cognitive functions and largely linked to conditions like schizophrenia, are hyperactive meaning the dopamine system can overemphasise certain stimuli, making them seem more significant than they are. This dopaminergic dysregulation in mesolimbic pathways also links back to reinforced delusions as this pathway projects to the prefrontal cortex. Thus, impairment to such a pathway can significantly impair cognitive control over delusional thoughts and reinforcing the imposter interpretation, especially relevant in cases of schizophrenia. Conversely, in neurodegenerative forms, such as that present in Alzheimer’s and dementia, there is reduced cholinergic activity, meaning a reduction in acetylcholine signalling. Acetylcholine (ACh) acts as a neurotransmitter crucial for various functions, including memory and so is needed to link memories with feelings of familiarity. Without it, the patient recognises the face visually, yet may struggle to feel the emotional bond that should come with it.

Similarly, while less likely, Capgras can also be linked with certain cases of severe depression due to its contribution in the distortion of emotional signalling. In extreme cases, the limbic system, especially the amygdala, can become underactive and can influence affective tagging and the emotional resonance that would ordinarily arise from seeing a familiar face is blunted or absent. This may cause some mental confusion and an odd instinct that something is wrong, not dissimilar to the “uncanny valley” hypothesis, and can cause your brain to fill in the gap with a delusional hypothesis – “they must be an imposter.” As if that isn’t enough, depression involves the dysregulation of serotonin and norepinephrine affecting both mood and emotional salience networks making people feel emotionally “flat”. Consequently, these low levels of serotonin may encourage dopamine hyperactivity in mesolimbic circuits, amplifying the strange, unfounded connections.

So, how can we control it? In psychotic disorders, as established, one key problem is the overactivity of dopamine. It can be managed by most antipsychotics, which block dopamine 2 receptors which reduce the flow of dopamine and can help alleviate the psychotic symptoms like hallucinations and delusions. On the other hand, in the setting of psychotic depression or bipolar disorder, due to the underlying imbalance of serotonin, antidepressants or mood stabilisers can have an effective role in maintaining a balance. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI) increase serotonin signalling, lifting mood, regulating dopamine levels and reducing depressive distortions of thought, while mood stabilisers (like lithium) regulate excitability of neurones, particularly effective in bipolar disorder, which can directly modulate the overactive dopaminergic pathways, reducing hyperdopaminergic state associated with the mania. Ultimately, though no single treatment has yet proven universally effective, treatment remains a work in progress, tailored to the individual and the complexities of their brain.

Capgras syndrome leaves us with an unsettling truth: our sense of reality is not fixed, but rather stitched together from fragile networks of sight, memory and emotion. A product of perception. And when those stiches loosen, whether by misfiring neurones or a chemical imbalance, the mind scrambles to fill in the gaps, even if that means rewriting family into imposters. And sometimes, even those we love most can become imposters, their faces familiar but their presence forever uncertain.