Do Animals Dream of Electric Sheep?

Dreaming remains as a mystery in science and psychology. Studies show that most mammals experience REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep, where dreaming occurs. EEG scans and behavioural studies suggest possible explanations, but no definitive answer has been concluded yet. Exploring dreams in humans and animals helps us understand sleep’s role in the organism’s day to day lives.

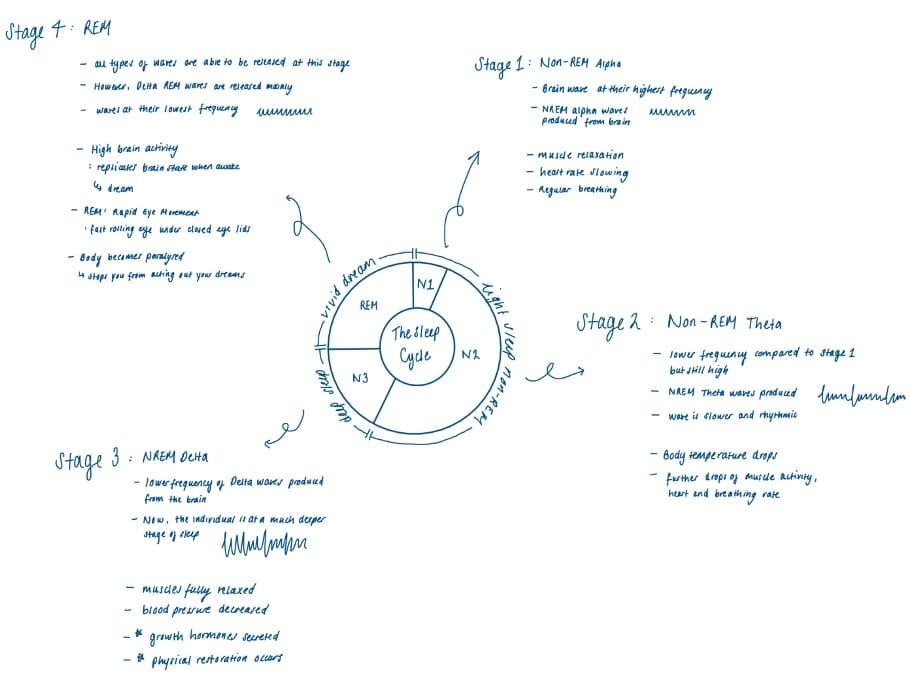

Humans follow a circadian rhythm, with ultradian sleep cycles occurring within it, regulating different sleep stages. An example of a single sleep cycle looks like this:

The Science Behind Dreaming

Dreams occur primarily during REM sleep, a stage of high neural activity similar to when being awake. The limbic system, responsible for emotions, becomes highly active. This explains why dreams often can have strong emotions attached to it. Whereas the prefrontal cortex, responsible for logic and reasoning, becomes less active, contributing to dreams’ abstract and illogical nature. Random neural firing may also influence dreams, as the brain attempts to interpret these signals through visual sketching.

Neurotransmitters also shape dreaming. Acetylcholine levels are high during REM sleep, supporting vivid dreaming, while serotonin and norepinephrine are inhibited. Since serotonin inhibits REM sleep and norepinephrine enhances alertness, their suppression may explain why dreams feel immersive and hyper-realistic.

Unconscious Mind

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory suggests that dreams allow visualisation of hidden desires and unconscious thoughts. His iceberg model proposes that suppressed urges surface in dreams, much like the divided nature of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Nightmares, in particular, may be linked to repressed desires or threat, highlighting the unconscious mind's influence on dream content.

Inspiration generation

Have you ever got stuck on a problem or struggled to come up with an idea for a piece of art or a solution to a math problem? Have you ever felt a sudden spark of idea light up somewhere inside your brain after you slept and dreamed? This is because we dream to solve problems, unconventional as it might sound. In your dreams, you place yourself in a world unconstrained by conventional logic; this allows your mind to come up with scenarios for problems in any possible route. These “pathways” in approaching the problem may not have been consciously considered while you are awake. John Steinbeck, an American author once said, “It is a common experience that a problem difficult at night is resolved in the morning after the committee of sleep has worked on it.”

Nightmares

Though dreams sound great, we might also get nightmares. These are significantly more common in people with high levels of stress, anxiety, trauma, PTSD or depression. You may wonder why we would get them if dreams were supposedly meant to be beneficial for us. Well, nightmares still do have benefits, like a sort-of “tough love”. Nightmares are an evolutionary survival mechanism that scientists believe help us to mentally rehearse dangerous situations. Similarly, the “Threat Simulation Theory” highlights that nightmares help us practice survival strategies for real life dangers.

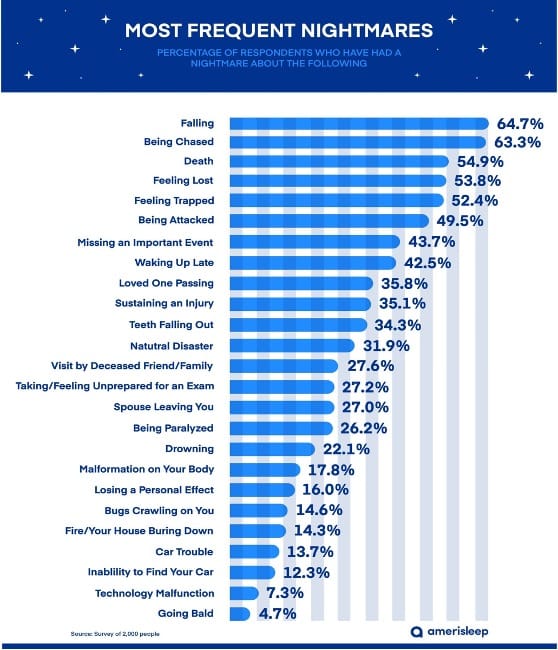

The graph is quite interesting, as personally I have experienced the top two most common themes - falling and being chased - multiple times. The reason for this dates us back to our ancestors, who faced threats from predators or enemies on a regular basis. Therefore, the nightmare of being chased may reflect an evolutionary survival instinct and mental rehearsal of escaping danger that have existed since the dawn of mankind. Falling is likely a reflection of your real-world emotional status, symbolic of losing control over something important, or represent a sense of self-doubt.

Recent Experiences

Dreams are also shaped by recent events, a term known as day residue. Studies show that people often dream about experiences from the past few days. The brain processes and stores new information during sleep, reinforcing essential details while discarding others. For example, students can dream about their studies, as the brain consolidates learning into long-term memory.

Lucid Dreams

Interestingly, some people have lucid dreams. This occurs when the prefrontal cortex remains more active than in typical dreaming, allowing self-awareness and sometimes control over the dream. Studies show increased gamma-wave activity in lucid dreamers, linked to higher cognitive processing. Additionally, acetylcholine plays a role in maintaining vivid dreams and awareness. Lucid dreaming may result from a hybrid brain state, where wakefulness and REM sleep overlap, enabling conscious control within the dream.

The Evolutionary Role of Dreams: preparation for threat

During REM sleep, the brain strengthens important memories while filtering out less relevant ones. Revonsuo’s Threat simulation theory (2000) suggests that dreams help us rehearse responses to danger, supporting survival instincts. For example, being chased and finding an escape route. This is similarly shown by a case study below, for animals too.

Dreaming in animals

If you’ve ever watched a dog sleeping, you may have noticed its paws twitching, ears flicking, or even a small bark. Scientists believe these movements are signs that animals, like humans, experience dreams. During REM sleep, like humans, the body suppresses muscle activity in animals. However, these often are not always perfect, causing minor twitches and movements to occur.

While we cannot directly ask animals about their dreams, we can infer their content based on behaviour and brain activity during sleep. Research shows that animals can and do experience REM sleep. The hippocampus, responsible for memory consolidation, springs to life during their sleep, suggesting animals replay daily activities in dreams. A study from MIT found that rats also exhibit brain activity during sleep that mirrors their actions while awake, which can be implied that they are able to dream about recent experiences (MIT, 2001).

Beyond memory processing, animals may dream of instinctive or imaginative scenarios, helping them prepare for real-life situations. This could be a form of survival rehearsal, allowing them to refine skills like hunting or evading predators.

A case study on a cat with REM sleep behaviour disorder (RBD) was seen with violent movements during REM sleep, such as sudden limb movements, aggressive posturing, and vocalisations. The study concludes that the behaviours reflect exaggerated dream enactments, showing that animals may dream of instinctive and dangerous scenes to boost their survival rate, according to Revonsuo’s Threat simulation theory (2000).

These findings suggest that, parallel to humans, animals may dream to process memories and rehearse survival skills in a risk-free way. The way we sleep is something ingrained into our biology. It is a fascinating reminder that deep down - despite the achievements, faults, and idiosyncrasies of man - we are still animals.