How Biology Dictates Lifespan

In the beginning, there were craneflies

About a month ago now, it was cranefly season. You know, the spindly, yet kind of cute, long-legged flies that were literally everywhere. The school was teeming with them. But now they’re all gone, nowhere to be seen, and we remain to watch generations of these little creatures live, reproduce and die over and over again. Slightly philosophical, and a little sad, I know, but the question remains: why do crane flies live for a couple of days then die off while we humans can live for over a hundred years? How does that work? Why does that happen?

Today, we’ll be exploring lifespans, and the reason for why they have such a dramatic variation in length.

Theories of ageing and lifespan determination

There are two main theories that come up with how ageing works. Programmed ageing, which state that ageing is genetically controlled, like a biological clock. This is true in many ways that we will move onto. The other is non-programmed ageing. This theory states that we do not have a genetic clock, but we age and die because of accumulated damage such as mutations and oxidative stress (an imbalance of antioxidants in the body that causes cell damage).

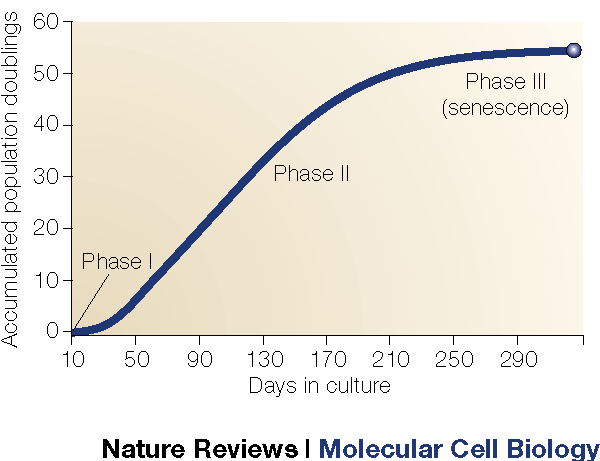

However, these theories both consider one cellular mechanism that unites them both, in a sense and in my view, makes programmed ageing seem far more likely to be true for many circumstances. As you probably know, our cells replicate continuously. When our cells replicate, they also copy out their genes. The issue is, when we copy out our genes, we are unable to replicate absolutely all of it meaning that we miss out a bit of genetic information every time. This is fixed by something called a telomere; a length of repeated base sequences – often AAA –that doesn’t code for anything. In cell replication, bits of the telomere are missed out rather than the gene, protecting our genetic information. However, over time it shortens and shortens and it comes to a point where the telomere has been completely removed exposing our genetic information. At this point, the cell automatically digests itself, ending its life cycle. After this, we are unable to code for proteins that we need. This could lead to various problems, like organ failure, weak bones, you name it. This can happen to any part of the body. The point at which this problem arises is called the Hayflick Limit.

Fancy stuff. Quite ominous too…

This is an essential piece of information we need to know. In humans, those cells with shorter telomeres live shorter lives, as they aren’t able to conserve their genetic information, and vice versa, assuming that no other complications are present.

In addition, over time our DNA can become and more damaged to to chemical exposure, mutations and UV radiation. While it can be repaired, restoration is not always 100% efficient, meaning that the accumulation of this damage can lead to inflammation, ageing, cancer and death. However, the concept of ageing is not quite as narrow as telomere theory; in fact, many other factors come into play. Time for the evolutionary stuff!

Evolutionary aspects

Another factor is antagonistic pleiotropy. This means that genes created can have beneficial effects early on in life, but harmful effects later on. Natural selection generally favours early-life success, even if it causes ageing later, as it means we are able to pass on our genes earlier. For example, take a little male rabbit. If he is producing lots of testosterone, he’ll have more muscle mass, be more competitive and probably a little more inclined to mate. This guy will go on to thrive in his earlier years, settle down, and have a big, nice family. However, increased testosterone can also cause cardiovascular issues such as plaque build-up, blood clotting and immune suppression, so he’s more at risk to die earlier on. But he’s done as nature intended, and has reproduced — so from an evolutionary standpoint, everything is fine. Keep in mind that antagonistic pleiotropy can happen due to many different hormones, not just testosterone.

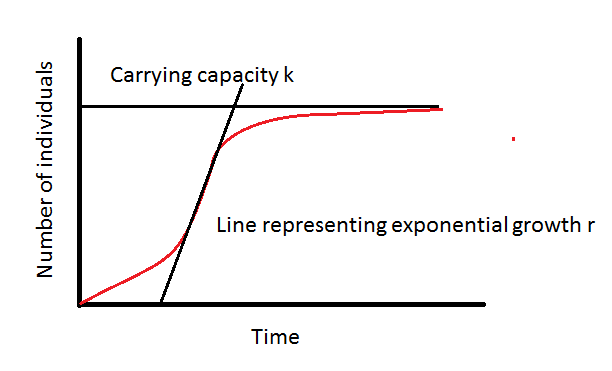

Let’s further investigate reasons why this manly, testosterone-fuelled unit won't live such a long life. Predation and environmental circumstances generally determine the lifespan of an animal more than anything else. Before we go into detail about exactly how this works, lets broadly summarise it for understanding. If an animal is more likely to be eaten, it has no incentive to invest in a longer lifespan. For example, the rabbit has many predators, like foxes, eagles, wild cats, and more. He’s constantly being hunted and odds are he wont live so long. Therefore, evolution has no reason to invest in mechanisms to make him live longer. Hence, rabbits are known as r-strategists as they produce many offspring and die young. The “r” here refers to the rate of reproduction — how fast a population can grow.

Another cool example I must bring up is the difference in lifespan between bats and mice. Mice are hunted by many things, and therefore don’t live so long. Bats can fly, creating a relatively safe environment in the air where not as many things can catch them. The Brandt’s bat is a prime example of this theory and can life up to more than forty years. And so, species with safe environments, like turtles whales and humans eventually evolve longer lives. These species generally produce few offspring, live longer and invest in survival. They are called K-strategists, where “K” refers to the maximum population size an environment can support.

In a nutshell, r-strategists maximise r (fast reproduction, many offspring, short lifespan). K-strategists maximise K (fewer offspring, high parental investment, stable populations)

Metabolic rate

The idea here is that animals with faster metabolisms have a faster rate of ageing. Smaller animals such as mice have high heart rates of up to 800BPM. For reference, a normal human resting heart rate would be 70-90BPM, depending on blood pressure. A faster heart rate means higher metabolic rate, which means that animals use more energy to stay alive. As a result, they also end up using more oxygen. While oxygen is essential for making ATP, it also produces harmful byproducts called reaction oxygen species (ROS), unstable molecules that damage DNA, proteins and lipids (like the ones that make up our cell membranes). Over time, this oxidative damage builds up, which contributes to ageing at the cellular level.

Genetic and cellular mechanisms

Time for some molecular biology. Every cell suffers from thousands of DNA lesions every single day. This can be from previously mentioned effects, such as oxidative stress and UV radiation, or predication errors and environmental toxins. If the lesions aren’t repaired, mutations accumulate and cells begin to malfunction, leading to tissue failure and accelerated ageing. Longer-lived organisms have multiple repair systems, that I’ll explain now.

Proteostasis

Often, proteins can misfold over time due to heat, ROS and random errors. Misfolded proteins clog cells and disrupt function – one of the major hallmarks of ageing. Long-lived animals maintain proteostasis, meaning they exhibit correct folding, rapid removal of damaged proteins, and quality control. Some key systems involved are chaperone proteins (which refold damaged proteins), proteasomes (enzymes which break down smaller damage proteins) and autophagy (a process that digests damaged organelles.) Proteostasis is essential for longer living, before DNA damage accumulates and becomes detrimental.

Apoptosis regulation

Apoptosis also has to be regulated. Apoptosis is programmed cell death which prevents damaged cells from becoming cancerous. However, too much of it leads to excess cell death, meaning tissue loss and ageing while too little of it leads to cancer and death. A balance is needed to optimise lifespan here.

Stem cell maintenance

Stem cells replenish tissues: skin, blood, gut lining, etc. In short lived species, the stem cells divide quickly due to high metabolic rate, and exhaust early. This means that their telomeres shorten fast and their organs decline. In long-lived species, cell division is slow. This means that the telomeres are maintained and regeneration lasts longer. In addition, there is less of a mutation risk since the frequency of cell division is relatively low.

Case study #1: Naked mole rats

These animals are exceptions of nature, living ten times longer than their relatives, which are mice. Naked mole rats live in oxygen-poor underground burrows, meaning they have to use energy efficiently. Their metabolism is low, and they can switch to fructose-based anaerobic respiration which reduces the oxidative damage we mentioned before.

These rodents are almost immune to cancer. They produce a unique high-molecular mass hyaluronan, which is a sugar-like substance that prevents cell from clumping into tumours. Crazy stuff. They also have very efficient DNA repair mechanisms, keeping their genome stable as they age, and have a very high expression of heat shock proteins, which help damaged proteins to fold correctly instead of clump. This species produces a ton of ROS, but their cells appear to be resistant to the damage, suggesting they evolved antioxidant defences or ways to tolerate damage without ageing effects. This is currently being researched.

Naked mole rats break almost every rule ageing. They’re literally just overpowered, immortal ground mice. They show that genetic and molecular defences can override metabolic and size-based expectations.

Case study #2: Greenland sharks

The longest vertebrates known to science. They have growth rates of just one centimetre per year, meaning that they reach sexual maturity at around 150 years old. They live in deep, cold Arctic waters (often below 1 degree C). These conditions slow all metabolic processes, kind of like cryogenesis. Their metabolism is extremely slow. Their tissues and organs operate at low temperatures, reducing cell turnover, DNA replication, and metabolic wear. The cold environment reduces oxidative stress, helping to preserve cells. Their delayed maturity and very slow reproduction suggest a “live slow, die old” strategy, which evolution allows in stable environments with few predators. This is a prime example of a K-strategist.

Case study #3: Craneflies

Our old, creepy looking buddies. Their lifespan is 1-3 days as an adult cranefly. They spend weeks to months as larvae, where most of their growth occurs. The adult stage is purely meant for reproduction, and once that is done, they die. Adults often lack a functioning mouth or digestive tract – no need to feed if they’re alive for around 48 hours. Their reproduction strategy is called semelparity – when an organism reproduces once in one season, then dies. It’s common in insects and some fish (like Pacific salmon). They also have delicate exoskeletons, limited muscle mass and weak flight capabilities.

They don’t take shelter either; they’re exposed to predators, wind, rain, etc. — hence the fact that they are oblivious to their surroundings and are rather clumsy. Females lay hundreds of eggs and die shortly after oviposition. The bodies of all craneflies degrade quickly from environmental stress; just like that, and they’re gone. A prime example that natural selection favours efficiency over longevity, and that sometimes, an organism just isn’t designed to live so long.

Conclusion

So, after our journey, we’ve finally found out why we have so many of those silly flies here at Charterhouse, and so much more. Lifespan isn’t governed by a single clock, but by a complex interplay of biology, ecology and evolution. From metabolic rate and oxidative damage to reproductive strategies and predator pressure, and how each species navigates trade-offs that shape lifespan. The more we understand about these patterns, the closer we get to understanding our own biological limits and how to push them.

Sources:

Cover image - Lane, 2013

Fig. I - Shay & Wright, 2000

Fig. II - Vetstream, 2023

Fig. III - Babu, 2018

Fig. IV - Basu, 2025

Fig. V - Preston, 2020